At the dawn of the 17th century a composer named Lodovico Viadana (c1560–1627) published a collection of sacred music for voices with “basso continuo.” He explained this term in his preface because it was the first time the words had appeared in print. In his collection, “basso continuo” meant occasional sharps and flats were placed over notes in the bass line–published in a separate volume from the voices and played on the organ–indicating some of the chords the organist was supposed to play.

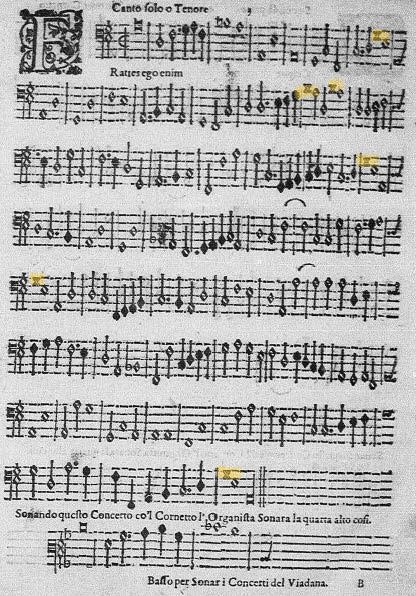

Here’s a page from Viadana’s collection with basso continuo sharps (which look like double x’s) highlighted:

But Viadana’s Cento concerti ecclesiastici … con il basso continuo (Venice, 1602) was not the first music to utilize the organist in this way, even though Viadana has often been called the “inventor” of basso continuo. Organists had been playing from separate bass lines, improvising chords over them or copying what the other parts were doing, by at least a quarter century earlier. Similar practices in secular music–using harpsichords, lutes, and various bowed string and wind instruments instead of organ–may even have been happening much earlier in the sixteenth century. But it was Viadana who first called it “basso continuo” and the popularity of his publication both inside and outside of Italy helped the name and the concept to stick.

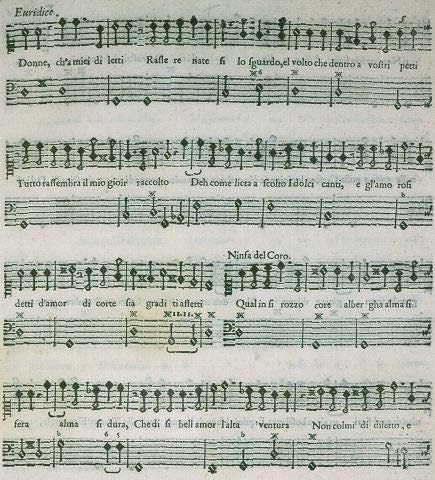

Before Viadana’s collection, however, music was already being written and published with figures–numbers indicating what chords to play over the bass line–and not just continuo flats and sharps. It wasn’t yet called “basso continuo” in these publications, but composers such as Jacopo Peri (1561–1633) and Giulio Caccini (1551–1618) were already using figures by at least 1597 in their operas and monody–a newly-invented type of secular vocal music with one (hence “mono”) singer. But these early forms of continuo were quite different from the harmonically-complex, numerically-abundant system that the art form evolved into by the 18th century: early basso continuo parts were sparsely figured (a trend that stuck around in Italy); used compound figures, such as 10, 11, and 14 (the same as 3, 4, and 6, respectively), that were quickly abandoned; and utilized sharps and flats alone to indicate semitone alterations to either the 3rd or the 6th above the bass (later such accidentals only referred to the 3rd). But changes happened quickly as the practice spread like wildfire across Europe and the compound figures and confusing use of accidentals were quickly replaced with a (mostly) well-codified system of figures. Even with late comers like France, who didn’t really start using basso continuo until the 1640s, almost all the music being written in Europe by the end of the 17th century included continuo.

Here’s part of a page from Peri’s opera Euridice–considered the first opera ever written for which we still have the music!–published in 1600, showing some figures:

But what is basso continuo really? Who plays it and what do they play? The performance of basso continuo almost always includes at least one chordal instrument (i.e. an instrument that is able to play chords) and one bowed bass-line instrument. The most common chordal instruments used were harpsichord, organ, theorbo, and lute, though there were other options, such as lirone (see video below), and the most common bowed-bass string instruments were viola da gamba and, later, cello (though here, too, additional options, like violone [see video below], were possible). Wind instruments such as the bassoon could also be used as bass line-playing continuo instruments, though they usually played in addition to rather than instead of the bowed bass instrument(s). The minimum number of continuo players was usually two (though solo voice with lute or theorbo was also common), but there was not necessarily a maximum number of players, especially for larger productions like operas.

Sidebar: Since the lirone and violone (depending on its meaning, as you’ll see) are both rarer, less familiar instuments, I wanted to share videos of them before we move on. Here’s a fabulous video on the lirone. . .

. . . and here’s one on the violone (and both its meanings) and how it might be used on occasion (not necessarily all the time) in J.S. Bach’s cantatas.

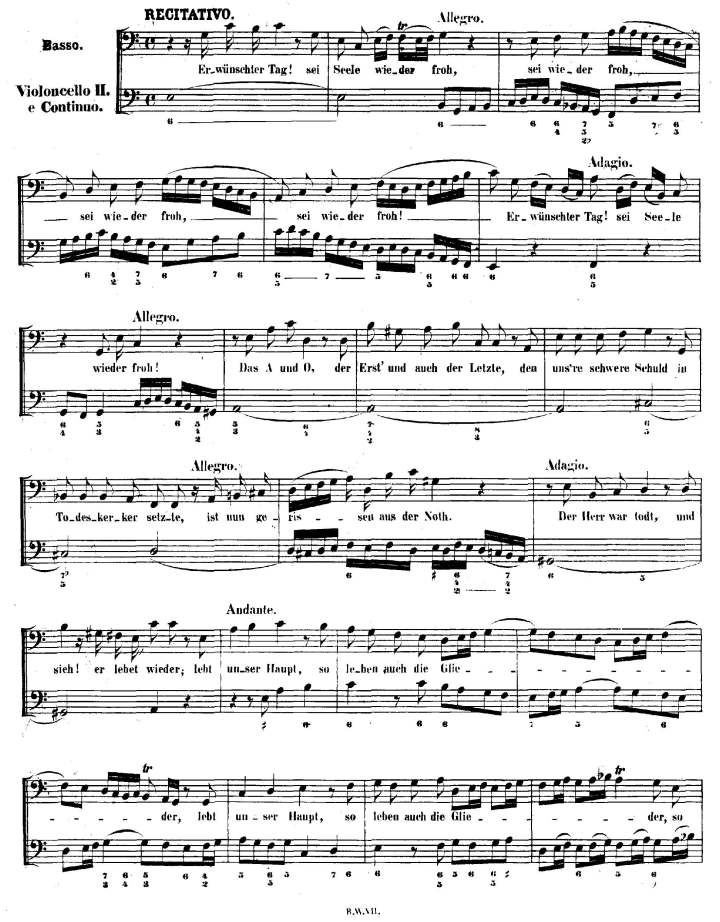

So what does continuo look like on the page and how do the players turn that into music? Here’s a page (Bach-Gesellschaft edition) from a recit in BWV 31, the Bach cantata that was discussed in my post on historical pitch (the original performing part from the Leipzig version [in Bb Major; see my earlier post for why] can be found here; the recit in that part starts on the fifth line from the bottom):

The continuo players all read from that single bass line with figures under it (or over it in the original parts). The figures tell the chordal instrument players which chords to play, but, somewhat counterintuitively, not which voicing to play each chord in, just which notes. For example, the first figure on the page is a 6, which means to play the note a sixth above the bass and also the note a third above the bass (the third is always implied if the figure is just a 6 alone). If I’m reading from the Bach-Gesellschaft edition, that means I play a C and a G in addition to the bass line E. But the figure doesn’t tell me which C and which G, or even how many Cs and Gs, I should play. This I decide on my own based on a number of factors, including how loud I want the chord to sound (the more notes, the louder the sound; the higher the tessitura, the louder the sound), the strength of the beat in the measure (more on this in another post), the mood (also called affect) of the piece, the range of the parts I’m accompanying (Do they have low or high tessituras?), and the acoustical properties of both the room and the instrument I’m playing (Does the room have an echo or is it “dry”? Is my instrument naturally loud or soft?).

In this case I’d probably play middle C and the G above it (in addition to the bass E), or possibly even middle C and both the G above and below it. This is because the chord falls on a strong beat (so I want a louder sound), the affect is happy and upbeat based on the text (also indicating I want a louder sound), and this open-position voicing helps me to stay out of the way of the bass voice part (open-position voicing means organizing the notes so that there are widely-spaced intervals, the opposite of closed-position voicing). Some of continuo playing is also a matter of taste and another continuo player might approach this chord differently. (It should also be noted that this chord, including the bass note, would be played with a short duration, only lasting about a quarter-note, instead of the full six beats notated on the page. This follows the practice called “short accompaniment,” which means that historically the chords accompanying Baroque recits were generally played short and were only notated with long-duration notes to save time when writing out the music by hand.)

Basso continuo playing is also the art of real-time contrapuntal execution, generally following all the rules of voice leading laid out by Johann Joseph Fux (c1660–1741). If you’ve studied music theory, these are the voice-leading rules you were taught and wrote exercises based upon–such as to avoid parallel fifths and make the seventh always resolve to the octave, etc.–whether or not you knew they were from Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum (1725). These are the rules we use to move from one chord to the next as keyboard continuo players (it’s a little different for lute and theorbo players based on the construction of their instuments), but unlike in theory class we do it in real time and improvise our chords as we go along.

There’s so very much more that could be said about how to play continuo–enough to fill volumes of books and require years of study to understand and apply–but I’ll save further discussion of this topic for later posts. I’ll leave you with two of my favorite continuo resources in case you’re itching to learn more or want to sit down at a keyboard and try our some continuo playing yourself.

First, here is a great website that shows all the different figures and explains what each one means. Especially helpful is the chart at the bottom of the page that lists all the figures in one place. Remember that the figures just show what notes go in a chord and not in which voicing to play them: robertkelleyphd.com/home/figured-bass/

Second, here’s my favorite treatise for practicing continuo: Principes de l’acompagnement du clavecin (Paris, 1718) by Jean-François Dandrieu. It’s in French, but you don’t need to know any French to practice the exercises. I love this treatise because Dandrieu teaches you how to play with proper voice-leading by writing out full figures (i.e. a number for every single note you would play in real life) in all his exercises. You would never see such thick figures in real music, but Dandrieu also gives you the “real world” version for every exercise (as well as a completely unfigured version), where you see far fewer figures but need to remember your voice-leading from the page before. I still love practicing from this book and I highly recommend it!